It’s no surprise that depression is prevalent among gay men. Alex Hopkins looks at the secrets and shame gay men often carry from childhood into adulthood. How do we deal with this to build a coherent and positive future?

I remember the moment vividly. I was lying on my bed, alone in my room. Downstairs my parents were laughing and chatting with my brother and sister. Over the previous three months I’d retreated upstairs. Much of the time I’d sit in the corner of the room, half-watching the TV. The rest of the time I would just stare at the ceiling, unable to move, contemplating what my future might be. After years of bullying at school, I’d finally begun to understand that those who taunted me on a daily basis, punched and kicked me, were those that I desired – or at least the gender that I was attracted to. This understanding threw everything that I had thought was right into turmoil. Coming out to my family simply didn't seem an option. I knew what my father’s views were – every time a gay person appeared on the TV he’d jeer at them. The only option, I decided as I lay there, was to hide my sexuality: marriage, children, a lifetime in the closet denying myself what I wanted, what I needed – what the Catholic Church had told me was inherently wicked.

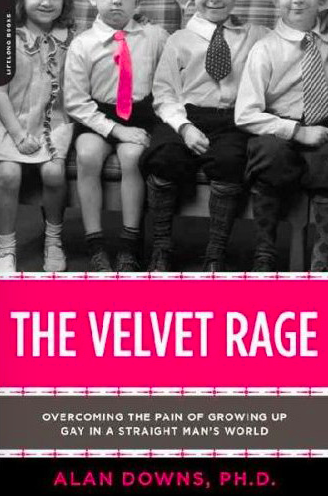

My experiences and feelings were not unusual among gay men back in the mid-1990s. If today it is easier for teenagers to come out, it still often remains the most frightening step they will ever make. Religion and culture play a huge role and for every joyful coming out story of acceptance we read about in the gay press, there’s another youngster hiding away contemplating suicide. Gay men, from an early age, therefore become extraordinarily good at wearing masks, putting on a front – at keeping secrets. In 2011 Alan Downs wrote what is perhaps the best account of this in his book The Velvet Rage: Overcoming the Pain of Growing Up Gay in a Straight Man’s World. Downs’ thesis was that gay men carry the deep feelings of shame surrounding their sexuality into adulthood, and as a consequence strive to achieve unrealistic standards of perfection – a veneer of conspicuous consumption and, of course, physical beauty. His conclusion, however, is bleak: no amount of possessions, sex or adoration can make up for the crushingly low self-esteem that haunts many gay men for the rest of their lives.

My experiences and feelings were not unusual among gay men back in the mid-1990s. If today it is easier for teenagers to come out, it still often remains the most frightening step they will ever make. Religion and culture play a huge role and for every joyful coming out story of acceptance we read about in the gay press, there’s another youngster hiding away contemplating suicide. Gay men, from an early age, therefore become extraordinarily good at wearing masks, putting on a front – at keeping secrets. In 2011 Alan Downs wrote what is perhaps the best account of this in his book The Velvet Rage: Overcoming the Pain of Growing Up Gay in a Straight Man’s World. Downs’ thesis was that gay men carry the deep feelings of shame surrounding their sexuality into adulthood, and as a consequence strive to achieve unrealistic standards of perfection – a veneer of conspicuous consumption and, of course, physical beauty. His conclusion, however, is bleak: no amount of possessions, sex or adoration can make up for the crushingly low self-esteem that haunts many gay men for the rest of their lives.

I didn’t so much explode out of the closet but gradually crept out, like a depressed zombie. I found the gay scene, the first place most teenagers head to after their big revelation. But it didn’t turn out to be the nirvana that I’d been looking for. Yes, on the surface everything was sparkling and new and exciting, but it did little to destroy the secrecy about my life which I’d harboured since childhood; indeed, the staggering availability of sex allowed me to cultivate a new secret life through cruising and saunas. We may come out to our parents and they may accept us, but how many of us feel safe enough to tell our families that we go to these places – spaces that are normalised on the gay scene? The result is that we frequently end up living double lives – an outward appearance of respectability that our families can cope with and then a hidden, darker world which we are unable to share with others. All of this complicates the search for “authenticity”, which Downs explores in his book.

Shame does not make for good mental health and it is no surprise that depression is so prevalent among gay men. But then look at how we behave towards one another: we have a tendency judge our peers mercilessly, dismissing anyone who doesn’t have the Holy Grail: the abs you can cut carrots on, the Popeye biceps; moreover, the concept of the Pink Pound convinces us that if we don’t have the high paid job or own a home we have in some way failed. Why is it, I have often wondered, looking around a club, that those with bodies of warriors are falling apart on the inside?

The phenomenon of chemsex and chillouts that is now dominating the gay scene can also, I believe, be attributed to the masks we wear. It’s hard not to see men hiding away for days in black rooms, stapled to their iPhones, as anything but a metaphor for disconnection and secrecy. It’s like the frightened child standing alone in the corner of the playground, desperately trying to avoid the eyes of his victimisers. But outwardly, of course, the Great Gay Show of Fabulousness must go on. In London – as in other major cities – the sight of a gay man popping into a needle exchange in a designer suit before travelling to his demanding, lucrative job in banking is sadly all too common. None of us feel that we can allow our guard to drop. We can’t bear to see what lies beneath.

The search for our authentic selves does not mean that we have to leave the type of sex – or the places we have it – behind. Gay men have always found new ways of relating to one another and living outside of the heterosexual model – traditions of “normality” that have historically persecuted us. This should be embraced. The crucial thing is to manage the self-destructive behaviours that we link with sex. Only by managing that childhood guilt and inadequacy can this be achieved. Perhaps one of the major issues is that now that we have won so many legal rights, we have lost that sense of a unified cause that connects us, that thing that can all fight for – a goal which gives us a purpose beyond the often fleeting nature of sexual encounters – encounters which too often do not lead to the intimacy which many gay men seem to be craving. The progress we have made towards equality should be something that we celebrate and should mean that the terror and isolation of the closet is just a dark memory. The problem is perhaps that that our interior lives are often out of synch with the unprecedented advances we have made in gay rights. We’re playing a game of catch up and urgently need to find ways of leaving our baggage in the past.

Editor’s note:

Hofstra University in New York has given approval for Dr. Vince Pellegrino, Ph.D. and his team to begin filming a documentary about his recently published book, Talk it OUT/No More Gay Shame. Check out the book on Amazon.com.

Join the conversation

You are posting as a guest. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

Note: Your post will require moderator approval before it will be visible.